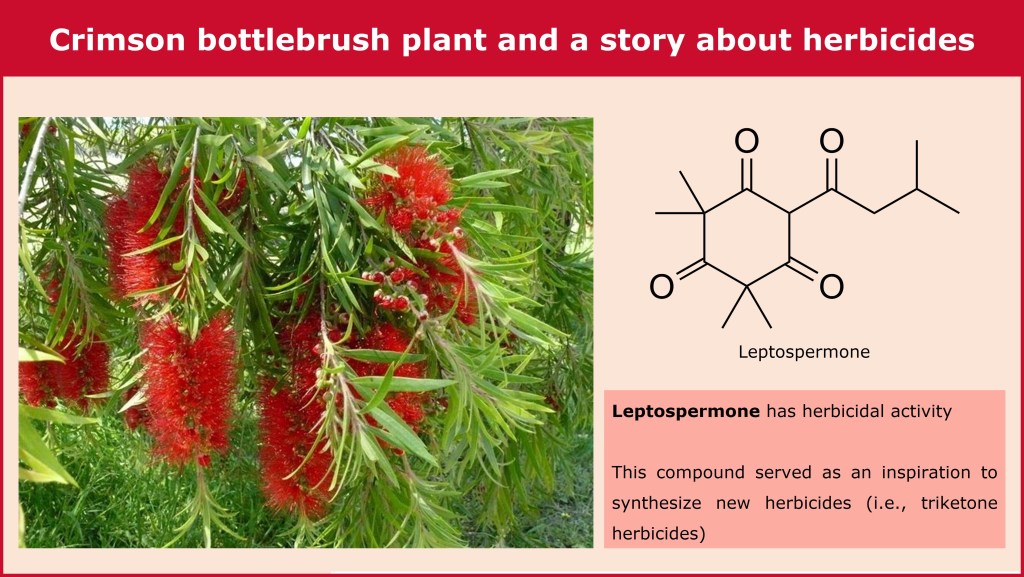

Let’s talk about a plant that is very commonly found in gardens in many areas of the world, but that is originally from Australia: the bottlebrush plant (looking at its picture, it is easy to understand why it is called like this). There are actually several bottlebrush species, all belonging to the myrtle family (Myrtaceae). Here, we will focus on the most well-known species, which is the crimson (or lemon) bottlebrush (Callistemon citrinus, now named Melaleuca citrina).

If you are a reader of this blog, you know already that plants always produce a complex mixture of different chemicals. In the case of crimson bottlebrush, we will mainly focus on a specific compound. Let’s start with a short story…

The story starts in 1977, when it was observed that there were not so many plants growing in proximity of the bottlebrush plants [1]. Researchers started therefore wondering what could be causing this effect. At this point, it is worth pointing out that this was not the first time that a phenomenon like this had been observed. Centuries before, distinguished personalities, like Theophrastus and Pliny the Elder, had already noticed it for other plants [2]. By 1977, it was known that chemicals were involved in this phenomenon. Therefore, people trying to understand the inhibition of the growth of other plants by crimson bottlebrush focused on the identification of the chemicals involved. They indeed discovered a compound produced by Callistemon citrinus, called leptospermone, which was actually an already known one and is also found in manuka oil [3]. However, its effect on other plants had not been studied yet at the time. It was shown that this chemical was impairing the growth and causing bleaching of grass seedlings [1].

Leptospermone was then a lead compound for the development of a class of synthetic herbicides, known as triketone herbicides, which were therefore inspired by the natural product [4]. The mode of action of both the natural and synthetic compounds was determined [4,5].

The concept that plants might be producing herbicidal compounds can be counterintuitive and of course you might be wondering how they protect themselves from the toxic effects. Several different strategies are involved; for example often these compounds are stored in cell compartments away from their molecular targets or, alternatively, the compounds might be accumulated as inactive precursors [6].

We have to bear in mind that, despite the common understanding of plants as inactive and somehow passive organisms, they are actually active parts of ecosystems, involved in the interaction not only with the environment, but also with other organisms, including other plants [7]. Therefore, it makes sense that they use chemicals to interfere with the growth and performance of neighbouring plants, a phenomenon known as allelopathy [8].

In case of the bottlebrush plant, the specialized metabolite which is responsible for the effect in nature has served as a sort of guide to develop new herbicides. The possibility of using natural products or natural product-derived chemicals as herbicides is linked not so much to their hypothetical low toxicity (remember that natural does not mean safe), but to the fact that evolution has been shaping these compounds for so long, that it is worth trying to get inspiration from them. Probably, the most convincing argument in support of the search for natural herbicides is linked to the possibility of finding alternative modes of action as compared to the ones of the currently available chemicals, a compelling need to counteract the ever-increasing herbicidal resistance problem.

One thought on “Crimson bottlebrush plant and a story about herbicides”